When I started studying Deep Tissue Bodywork in 1983 the common perception in the U.S. was that therapeutic change couldn’t manifest through touch. Even Acupuncture at that time was commonly considered akin to witchcraft. Talk therapies had reached some general acceptance within the previous ten years and by the early eighties, you didn’t have to go stark raving mad before sitting down with a psychologist. In the U.S. the perception that touch can be therapeutic is even now considered startling to many people and I think (hope) we have only recently reached the level of understanding and social acceptance that talk therapy reached around 1980.

In Europe, the situation is quite different. In the last 30 years, the Health Care System has firmly embraced the modern traditions of therapeutic touch. Insurance reimbursements for Manual Therapy are routine, and for many conditions, invasive procedures are held as a treatment of last resort after Manual Therapy remedies have proven ineffective. The cost savings to the Health Care System can be astonishing as a few thousand euros of touch therapy often produces a better outcome than a few hundred thousand euros of surgery and recovery services. Manual Therapy’s capacity for identifying and resolving the root causes of disease rather than surgically or pharmaceutically reacting to symptoms additionally improves outcomes and reduces costs. In a “not for profit” medical model, the logic of turning to Manual Therapy as a treatment of first resort for many conditions is unassailable. The European Manual Therapy training institutes are by far the most established and most current research is coming out of the EU.

The curious thing about Manual Therapy is that it is a distinctly Mid-Western American traditional medicine. Frontier healers in the 1800s codified skills in Bone Setting, folk medicine, and Native American knowledge into a general practitioner understanding that developed into schools of Osteopathic and later Chiropractic medicine. These traditions were the standard for care for rural Americans into the mid-1920s.

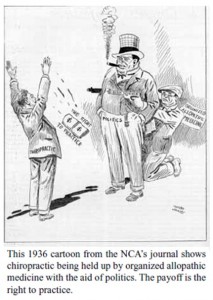

The brutality of the 20th century quickly advanced the state of the art of battlefield medicine. Additionally, the 1919 Spanish Flu, killing ~50 million people worldwide within a few months, highlighted the limitations of Manual Therapy and vastly increased the resources committed to triage medicine. Combined with the efficiency of throughput implicit in treating symptoms pharmaceutically, by 1925 a surgical/chemical medical philosophy known as Allopathic Medicine began to dominate care in the US and later in Europe. At that point, the belief took hold that it was merely a matter of time until we would live disease and pain-free Allopathically, through the wonders of science. The concurrent philanthropic work of J. D. Rockefeller dwarfed all other influences and was solely focused on bolstering Allopathy over all other healing arts. His vision of health care for all Americans was sourced from his friend Henry Ford’s assembly line economies of scale. He picked and choose what was, and was not, health care and then put his gargantuan financial and political weight behind those decisions. He successfully legislated to criminalize modalities not making his cut. It took at least 50 years for other modalities to begin to crawl out from under this onslaught (e.g. Chiropractic and Acupuncture only began to gain political stature after the 1970s).

The incredible scientific advances of the past century have ensured the continued dominance of this medical model over the labor and skill-intensive specialized subset of therapeutic protocols known as Manual Therapy. Additionally, the for-profit marriage of health care providers to insurers sidelines Manual Therapy in favor of treatments where obvious economies of scale reside. If you are unlucky, your health issue will not fit into one of these “silos” and you are relegated to palliative care until your issue progresses to a point where you can be “plugged into” the system. Perhaps the best way to distinguish Allopathy from Manual Therapy is that the Allopath focuses on specific dysfunction (disease), whereas the Manual Therapist looks at structure first and then function in relation to structure, considering the dis-ease. The assumption is that most musculoskeletal issues will resolve from improved structural/functional integration.

In the United States through the 20th century, the knowledge base of manual techniques continued to expand, albeit “under the table”, with many individuals contributing new discoveries and making profound connections between different modalities. Prominent figures include Ida Rolf, George Goodheart, Frank Chapman, and Terrance Bennett. By the 1980s a broad base of knowledge spread over many different modalities was beginning to be published and become more widely accessible. In addition to Chiropractic and Osteopathic Medicine, Applied Kinesiology, Rolfing, Travels Trigger Point work and many other modalities made foundational contributions. Other, more recent major contributors to furthering the state of the art include John Upledger, Leon Chaitow, Tomas Meyers, Jean-Pierre Barral, and many others. Most current research is conducted in Europe, Great Britain, Canada, and Australia, where a socialized cost reimbursement model makes the true cost, rather than the apparent cost of treatment easier to discern. The state of the art of current research is collated in:

The Journal Of Bodywork and Movement Therapies

and the ongoing work of the:

The biggest challenge with Manual Therapy research is that the techniques are difficult to standardize, and consequently analyze. Manual Therapy can essentially be reduced to the skill and talent of the practitioner and the results they achieve with their clients. It is a complex skill set that takes a lifetime to master and requires innate talent to bridge that gap. In touching thousands of patients, it becomes easily apparent how tissue responds to a stimulus, both locally and globally. With experience, it is easy to guide the tissue to more functional relationships. It is a mysterious skill to practice, sometimes producing “miraculous” results until the practitioner matures to where those results become simple and obvious. Experienced Manual Therapists may consider this point to be prior to reaching ~10,000 client hours. Teaching this skill is challenging, and there is no substitute for practice.